Originally posted on The Otter ~ La loutre, May 17, 2017

When Monsanto spent $1 billion in 2013 to purchase Climate Corporation, its climate data, and its algorithms for using machine learning to predict weather, everyone from farmers and insurance companies to technologists and The New Yorker concluded that agri-business believed the climate science consensus: climate change is real and its introduces real risks to business. One century earlier, another major Western agri-business (Archer-Daniels-Midland or ADM) produced their own cutting-edge weather and crop forecasts, mainly in an effort to reduce the risk of what it called “weather markets.” By investing in environmental knowledge production, these companies revealed how they understood both local environments and international climate sciences.

Business signals its knowledge about the environment at many scales, from local family farms to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. When Reagan-era Secretary of State, George P. Shultz, and Climate Leadership Council president, Ted Halstead, recently advanced what they call The Business Case for the Paris Climate Accord, their message was simple. Since top US businesses support the Paris climate agreement, Donald Trump should reject any claims that climate change is a hoax and he should remain at the table in Paris. They argued that he should use it to advance his global diplomatic priorities, dismantle the Obama administration’s climate regulations, and “help reduce future business risks associated with the changing climate.” Conspicuously absent from this agenda are any of the ethical and other traditional reasons for stopping runaway climate change and mitigating the harmful effects it will have on humans and the non-human environment.

And that is, of course, the point. This New York Times op-ed is part of the journal’s pivot toward legitimizing climate change perspectives from outside the broad consensus of climate scientists. The editorial board now favors conservative voices on climate like the Climate Leadership Council precisely because “it is not made up of the usual environmentalists.” Clearly, progressives support a fair consideration of multiple perspectives, and this should include different political leanings, but one troubling new approach to truth in 2017 seems to argue that scientists and other expert voices should get no more attention than anyone else’s. Unless, that is, they have popular appeal. The Times defended hiring Bret Stephens, a pariah among climatologists, partly because “millions of people … agree with him on a range of issues.”

When a group presents a “business case for [insert environmental issue here],” they are arguing that if business approves of said environmental position then the market approves, and if the market approves then the consumer approves. And the customer is always right, amiright? Joking aside, this remains one of the great questions of our time. What is the role and responsibility of business in sustainability? Some put it in the back seat, and others argue that when the interests of capitalism and environmentalism align there could be no greater consensus. This appears to be the position of the New York Times, which isn’t exactly a populist rag. The chief exception to the anti-expert policy is the chief herself – the CEO. In November 2016, US voters made a CEO the Chief-in-Chief, and now they wait to see what business will do with the Paris accord.[1]

One group that tends to avoid the business case is our own tribe of environmental historians. As a field that cares very much about the environment we are good at talking to business, but we must also learn from organization and contribute meaningful analysis of it. This is essential considering we spend so much of our time describing how human organizations (usually private enterprise) interact with the non-human environment. Conversely, business historians are often guilty of ignoring the non-human environment and human attitudes toward it. However, interdisciplinary bridges (ecotones?) have been developing between these fields, beginning with an article by Christine Meisner Rosen twenty years ago. In 1999, Rosen and Christopher Sellers edited a special issue on the environment in the Business History Review, a journal whose stated interest now includes exploring “the relation of businesses to political regimes and to the environment.”

I think this leaves us with exciting opportunities and with our work cut out for us. Environmental historians seem increasingly interested in the relationships between business and the environment in articles in Environmental History, Environment and History, and other journals. For example, Rosen reiterated her call in Environmental History in 2005, and Sam White’s 2011 excellent study of “Capitalist Pigs” argued that “we need to study the history of pigs themselves as well as the history of capitalism.”[2] Recent books and edited collections have also set out to examine the issue, including the new Histories of Capitalism and the Environment Series, edited by Bart Elmore. In his own monograph, Citizen Coke, Elmore shows how business interacted with natural resources, or in the case of Coca-Cola how they pioneered the outsourcing of those interactions to other companies. In Green Capitalism? Hartmut Berghoff and Adam Rome bring together thirteen essays on twentieth-century business that attempt to answer the question: can capitalism be green – or at least greener?

Canadians will note that most of these explicit connections between business and nature have been made in the context of urban environmental history, although some examples in northern forestry, mining, and hydroelectricity bring the business approach beyond the metropolis and into the farm and resource frontiers.[3] Recent pioneering work on mining includes Liza Piper’s work on hard rock mining in Canada’s Northwestern lakes and Jessica van Horssen’s work on Asbestos, Quebec.[4] More non-urban approaches are appearing in a new special issue of Business History edited by Andrew Smith and Kirsten Greer.[5] Canadian historians will be interested in the recently published articles on environmental knowledge in the Hudson’s Bay Company records, the Ontario cheese industry, and Alcan in Greenland. All of these studies consider ways that organizations tried to understand and manage the natural world.

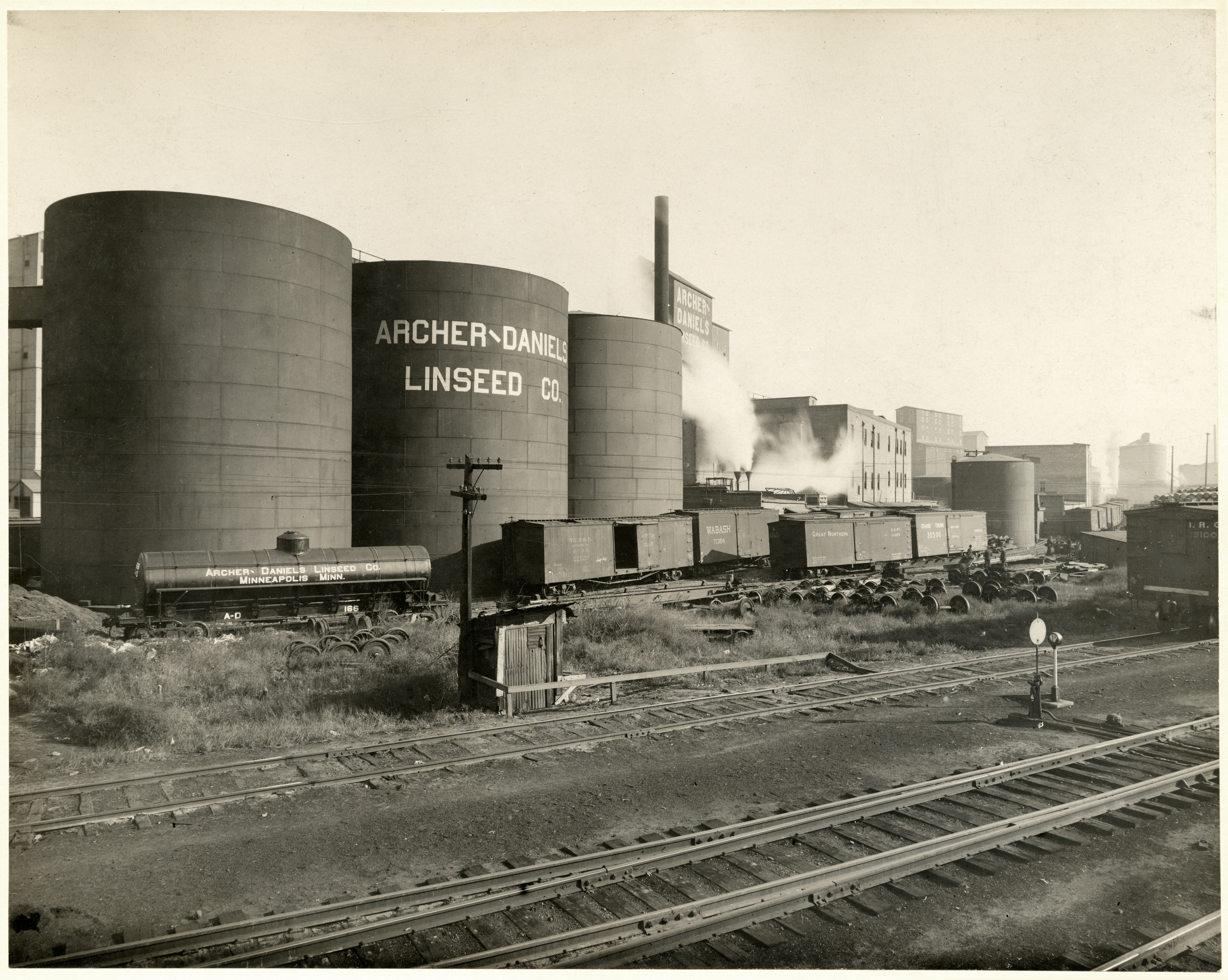

The business case for environmental history argues that nature looks differently when we examine it with company records and within the context of the firm. My study of the economy of knowledge in agri-business, focuses on Archer-Daniels-Midland Linseed Company (ADM), a notoriously secretive company that started in Minneapolis and has since become one of the big five multinational firms in the agrifood sector.

The history of ADM’s response to price volatility, supply chain problems, and trade policies tells us about the way businesses understand climatology and develop environmental knowledge. Like Monsanto and the Climate Leadership Council, they were predominantly concerned with risk mitigation. But where there was risk there was profit, and the linseed oil business included some of the leading names in the chemical sector, including Lyman Brothers in Montreal, the Rockefellars’ American Linseed Oil, Sherwin Williams, and Spencer Kellogg and Sons.

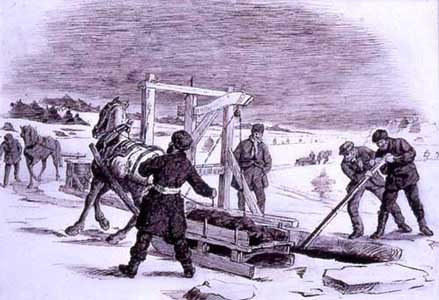

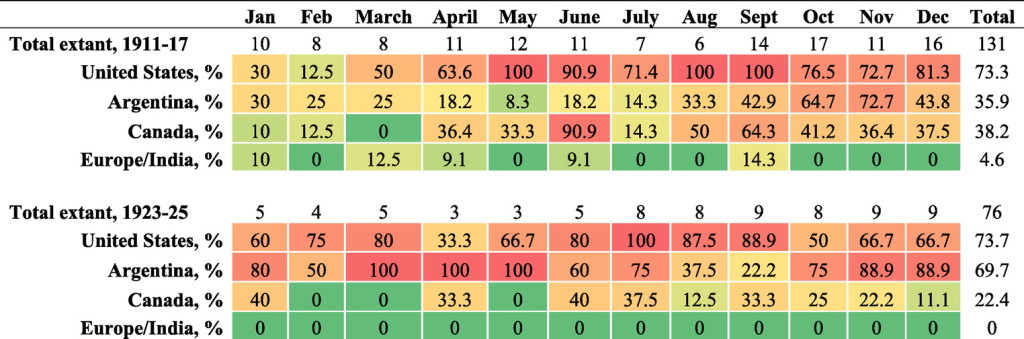

As a relative newcomer, ADM found a niche by providing crop and other environmental information to the trade (Figure 2). Linseed oil companies bought flax seed and flax seed futures in a massive grassland frontier (the Northern Great Plains, the Canadian Prairies, and the Argentine Pampas) with limited knowledge of those regions’ agroecosystems and even less about their climates. Crop knowledge was extensive and growing in the late nineteenth century, but climate knowledge was limited and retreating, because of underfunding and spurious theories about solar radiation. Meteorological forecasts were only good for 48 hours, and although Farmer’s Almanacs were very popular, their forecasting methods were secretive and studies have shown that they were really no more accurate than a coin toss.

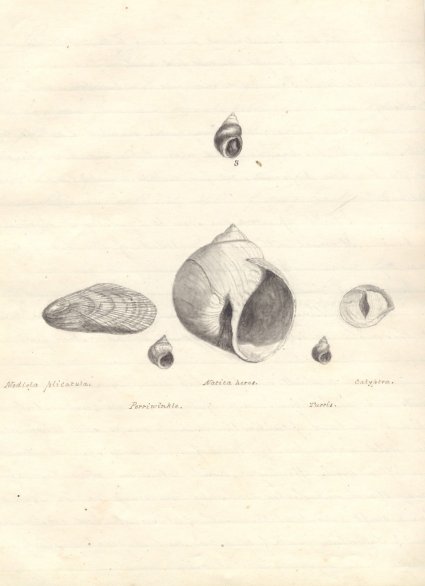

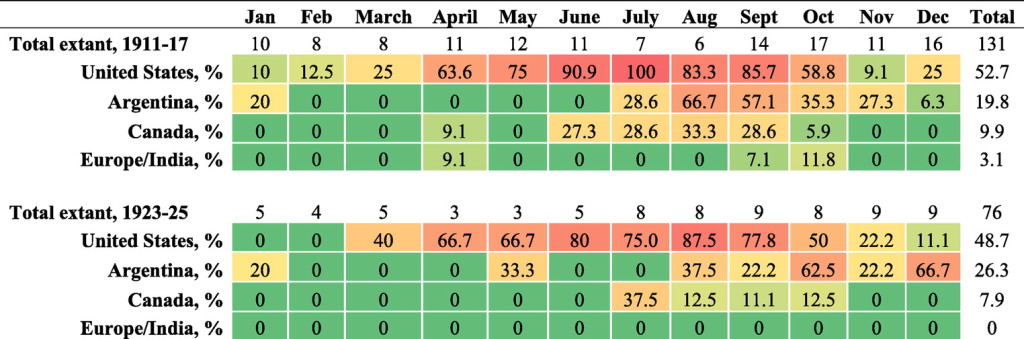

ADM realized that in the period between sowing and harvesting, the price of flax was “a weather market.” But their records show that businesses in the grain and oilseed sector created extensive knowledge networks to gather crop and some climate information in almost real time. Unlike the meteorological offices or the almanacs, ADM, was aiming for the respect of a much smaller business circle, and they therefore maximized data and minimized predictions. They mentioned US weather in about half of their circulars (less for other countries) and they predicted weather in very few of those cases (Figure 3). They were more bullish with crop forecasts, but the circulars show that they rarely reported weather forecasts. The weather that they did report was current conditions, and it was mainly in regards to the Northern Great Plains crop during the critical maturing and harvest months (June–September).

As my longer article on ADM’s response to “weather markets” outlines, the company was deeply invested in place and its business decisions were shaped in part by its longer commitment to the Northern Great Plains. Its larger role in the knowledge economy was influenced by its position on crop and climate science; the company distrusted government crop forecasts and disregarded meteorological forecasts. ADM’s respectability depended on accuracy, but as the almanacs (and recent politicians) show, you don’t need to be accurate to be popular.

[1] At the time of writing, some important signs from the US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson suggest that US intends to support the Paris agreement. Mike Blanchfield, “Freeland praises Tillerson’s work on Arctic Council climate change statement,” CBC News, May 12, 2017 <accessed May 16, 2017>

[2] Christine Meisner Rosen, “The Business-Environment Connection,” Environmental History 10 no. 1 (2005): 77-79; Sam White, “From globalized pig breeds to capitalist pigs: a study in animal cultures and evolutionary history,” Environmental History 16, no. 1 (2011): 94-120, 112.

[3] Magnus Lindmark and Ann Kristin Bergquist, “Expansion for Pollution Reduction? Environmental Adaptation of a Swedish and a Canadian Metal Smelter, 1960–2005,” Business History 50 no. 4 (2008): 530-546; Christopher Armstrong, Matthew Evenden, and Henry Vivian Nelles, The River Returns: An Environmental History of the Bow (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2009). Business History Review’s 2016 special issue on agribusiness also contains many significant rural contributions.

[4] Liza Piper, “Subterranean Bodies: Mining the Large Lakes of North-west Canada, 1921-1960,” Environment and History (2007): 155-186; Jessica van Horssen, A Town Called Asbestos: Environmental Contamination, Health, and Resilience in a Resource Community (UBC Press, 2016).

[5] The special issue stemmed out of a 2014 meeting that enjoyed support from NiCHE and some very helpful commentary by Christine Meisner Rosen and others.