This article originally appeared on The Otter ~ La loutre, 1 November, 2016

Canadians have been hitting above their weight in the area of geospatial analysis since the development of the Canada Land Inventory and the world’s first Geographic Information System (GIS) in the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly, environmental historians and historical geographers have made great gains in Historical Geographic Information Systems (HGIS) research over the last decade, including several NiCHE projects, a 2014 edited collection, and now the Canadian HGIS Partnership. Canada is big. And in typical high modernist fashion, postwar scientists trying to fathom it ignored the knowledge of the rural, northern, and indigenous people who understood its land and water. Instead scientists turned to digital tools like GIS to examine and measure the nation. In what we believe is a post-normal and integrative approach, environmental historians are now both using the software and critiquing the normative processes it helped to create. But Canada is still big; its libraries, students, and other knowledge resources are very far afield. Our communities of digital scholars employ digital tools to collaborate and communicate our results across the continent. This post focuses on the students using these tools and the new ways historians are teaching HGIS online. This kicks off a series written by NiCHE and CHGIS collaborators on geospatial tools and analysis for Canadian historians.

I teach environmental humanities at Arizona State University, and although I am a Canadianist my Southwestern students are usually interested more in my knowledge of digital history, HGIS, and environmental history. I teach the many ways that digital tools allow us to explore the importance of place in the modern consciousness. At first I worried that I wouldn’t be able to shoehorn my Canadian research into my American courses, however, I discovered that place histories are surprisingly versatile in the classroom setting. They travel well in the digital medium. I also learned that many of my students are not Southwestern at all, mainly because of ASU’s growth in online teaching. In my first year I taught two courses to online MA students, one in Digital History and the other in GIS for Historians.

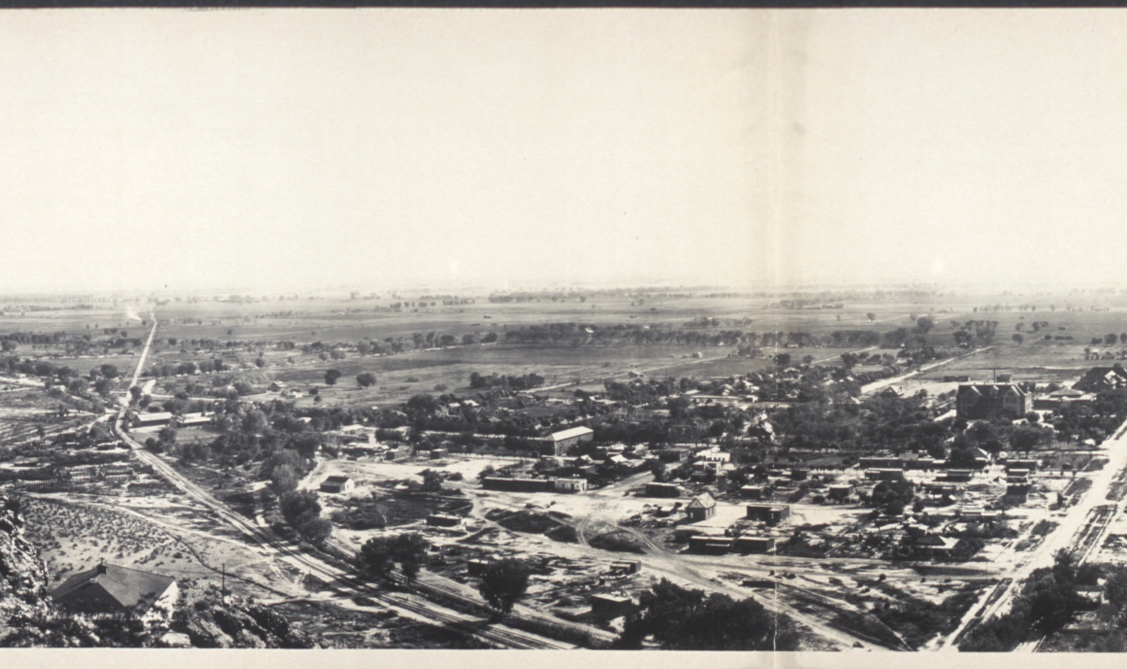

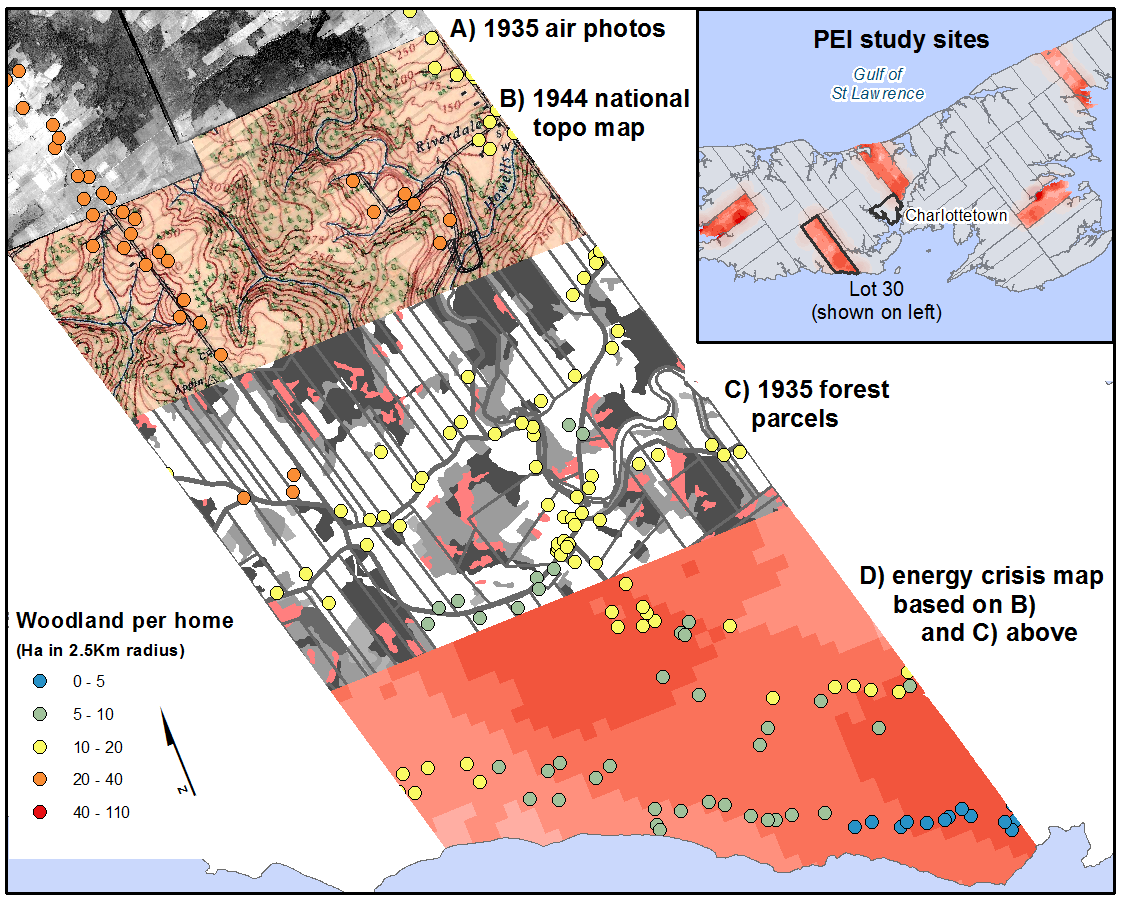

In the HGIS course, I decided to lead students through place history exercises, but I wanted to teach them using my familiar Canadian examples and then assign them group projects in the relatively uncharted territory of the Phoenix Metropolitan Area (PMA). So in the summer of 2016 twenty-six MA students learned basic GIS entirely online, they applied the skills they learned using data from Prince Edward Island, and they then worked in groups to recreate the historical geography of three “lost neighborhoods” in parts of the Southwest where many had never been.

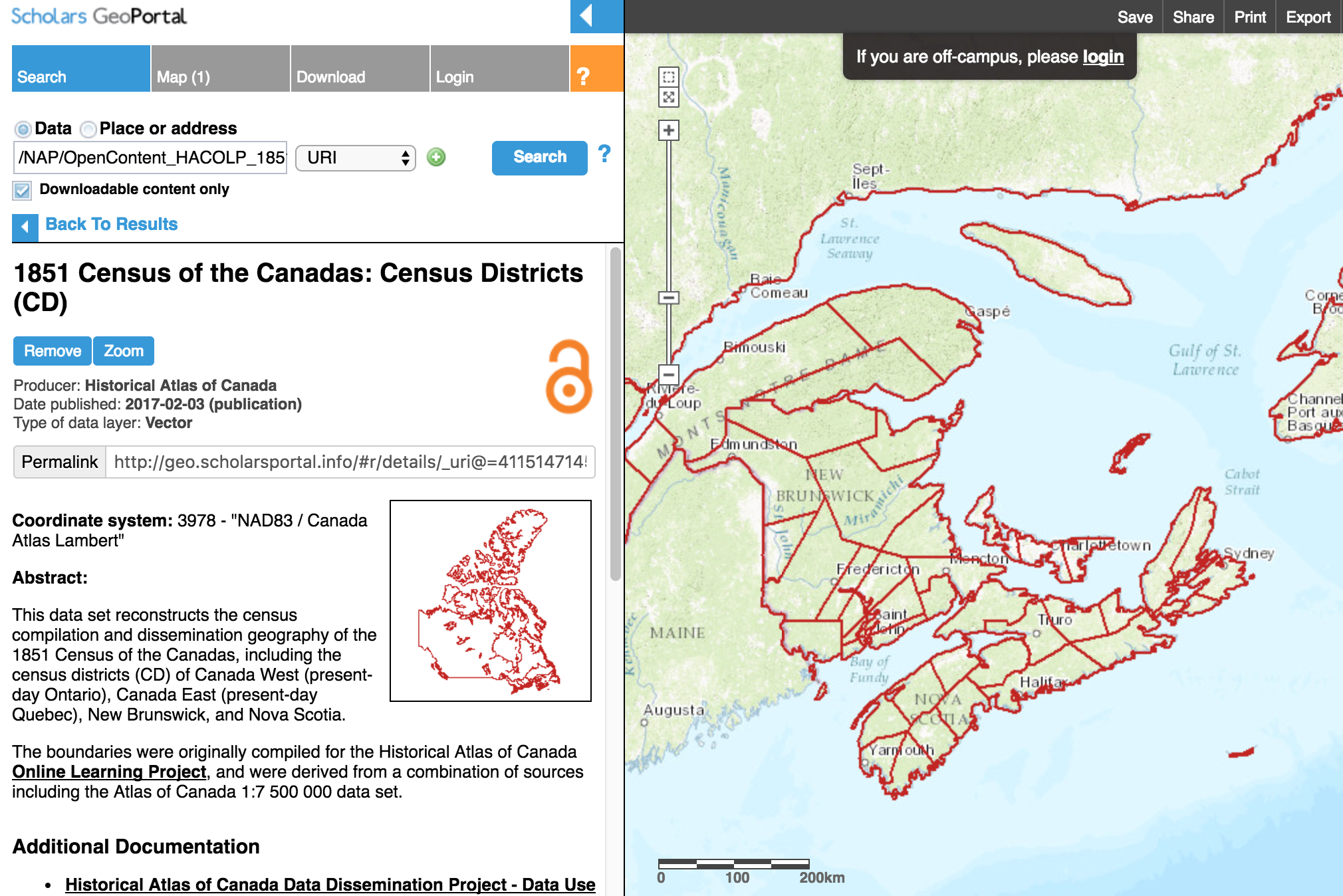

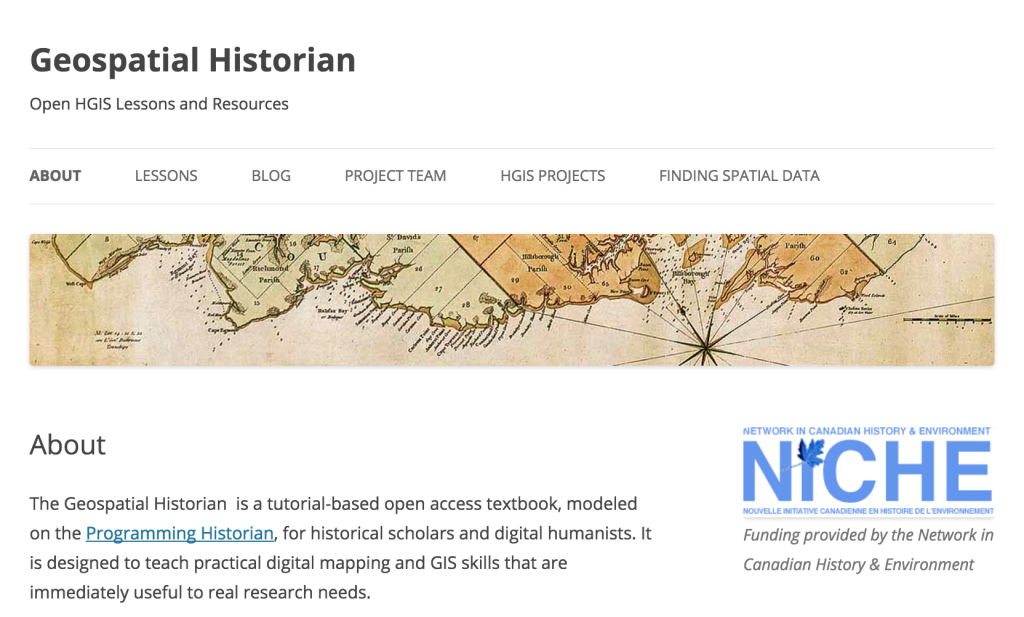

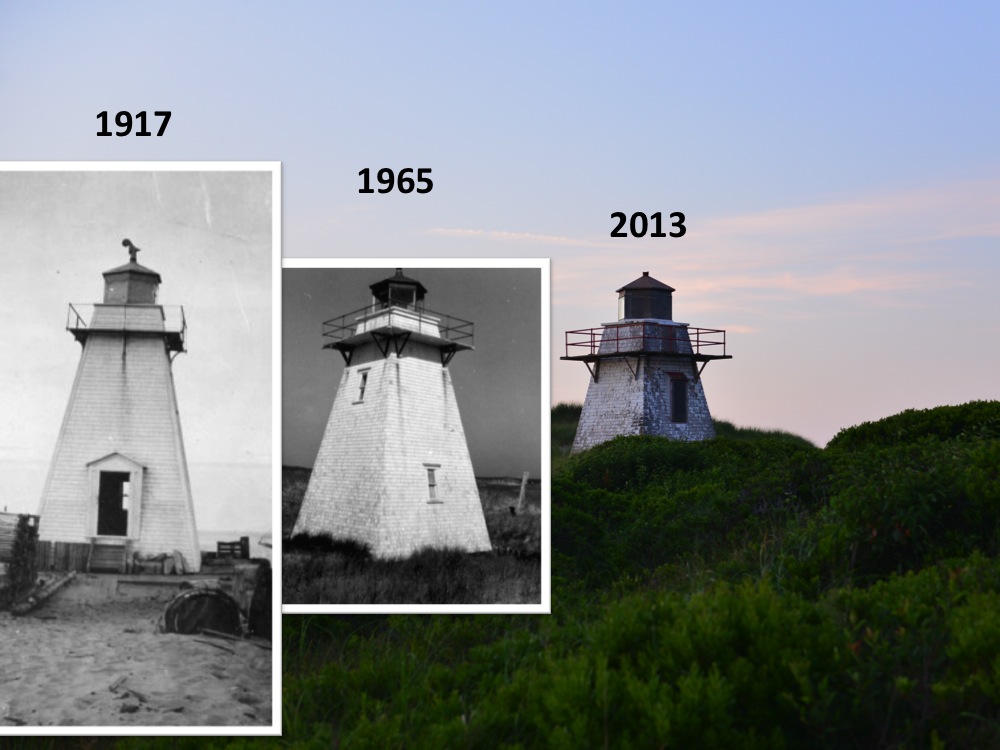

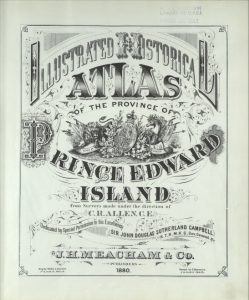

Learning HGIS online was possible in part because of The Geospatial Historian open access tutorial, which I explain below, and because of open source software like QGIS. Students were eager to try the software and apply it to the sample data from Prince Edward Island through the Geospatial Historian lessons. By working on new PEI case studies they were able to process historical maps from an 1880 atlas, “ground truth” their results in GIS, and then digitize the residences recorded on the maps. Students learned to georeference historical maps and determine whether the mapped features were appropriate for analysis at various scales. They worked individually, but the end result was a collective map of rural settlement patterns in the province.

The students then turned to original work in the Phoenix area, and they eagerly tackled the tools and the projects because they recognized the importance of this work. The three neighborhoods we selected reflect some of the most critical social issues of our time: racism in residential schools, like the Phoenix Indian School, and poverty, migration, and segregation in Mexican American barrios in the Southwest borderlands. Two of these neighborhoods are virtual ghost towns in the middle of large Southwestern cities, yet in different ways they play host to their former residents.

The Phoenix Indian School was one of the largest and longest running residential schools in the United States. It was decommissioned by the federal government in 1990, but nearby Native communities are very active in its restoration, and recent efforts have led to historic preservation projects. One of the groups in

my HGIS class made wonderful use of the technology and the digital records to recreate some of the important changes in and pressures on this now very valuable piece of Phoenix’s real estate. HGIS and the online forum facilitated their research and energized their work. And like the other teams, the Phoenix Indian School group asked local members to visit the site. These two students surveyed the site in the summer heat, and they interviewed local experts like Patty Talahongva, a former residential school student who is now working to build a memory and healing project in one of the school’s main buildings. (See the students’ Phoenix Indian School website here)

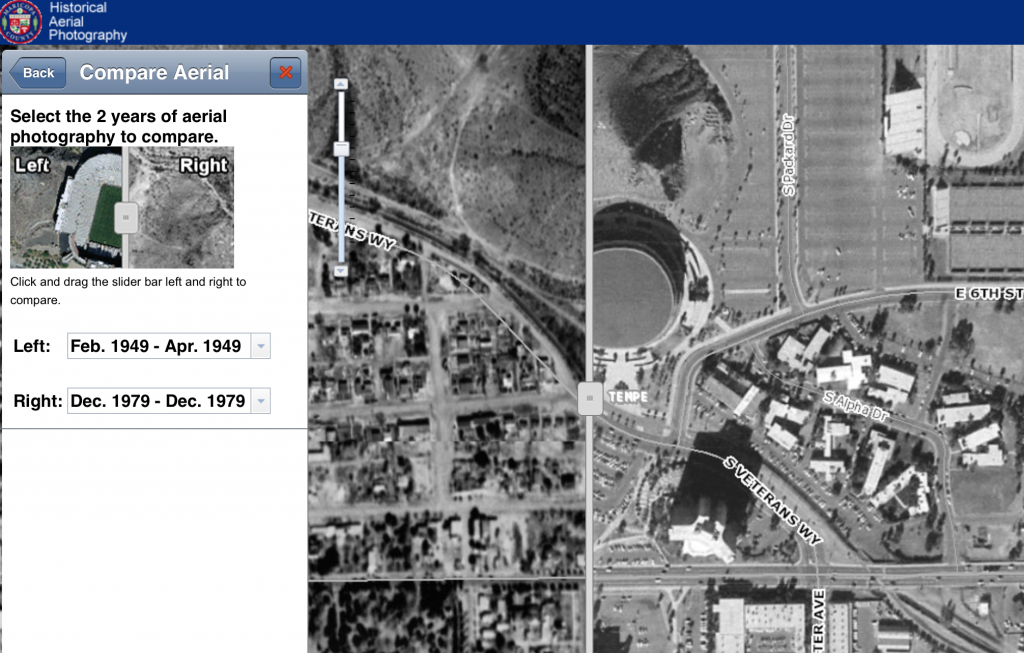

San Pablo was a Hispanic barrio completely erased from east Tempe, Arizona in the 1950s in order to make way for the expansion of ASU. Students in the San Pablo study group used several innovative methods, including Prezi videos and historical aerial photo interpretation to display the way this community lived in the early twentieth century. In some ways, San Pablo’s inhabitants return as part of the New American University’s initiatives to encourage enrollment from students of color and to make the student body representative of local demographics. (See the students’ San Pablo website here)

The third neighborhood, the postwar migrant barrio Victory Acres, is the only one of the three “lost neighborhoods” that still exists in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. However, it was so radically reshaped by urban development in the 1970s and highway construction in the 1980s that in 1993 one local historian claimed that “Victory Acres shows just a few vestiges of the old barrio.”[1] Using a combination of local histories, historical aerial photographs, census data, and site visits, the students in this group reconstructed Victory Acres before and after the development of a major highway that isolated the neighborhood and removed many of its houses. (See the students’ Victory Acres website here)

Historical GIS is an optimal tool for researching and rebuilding lost neighborhoods, and it is possible to teach these skills in the classroom and even online. However, there were still many roadblocks ahead of us in this course. GIS training usually requires expensive software and many hours of technical training in a lab setting. Conducting historical geography projects often requires people with local connections to visit archives, find maps and other non-digital historical sources, and “ground truth” maps to explain problems in cartography, georeferencing, and historical data. We had limited technical support, no on-the-ground local supports, and only six weeks to run the course. Most of the students had little or no experience with GIS or historical geography. Furthermore, I was traveling and the course would be taught almost entirely away from my desk. It is remarkable that the students accomplished as much as they did.

Fortunately, Jim Clifford, Daniel Macfarlane and I had produced an online open access tutorial designed to introduce historians to simple GIS project development and analysis. The website is called The Geospatial Historian, and following the model of the Programming Historian it was designed to teach students to use open source software for doing digital history. In June I presented the Geospatial Historian website at the Canadian Historical GIS network mid-term meeting (see slides here), and I discussed my plans to use it for teaching at ASU.

Another key to the course’s success was securing historical data from both ASU Library’s GIS data and Maricopa County’s Historical Aerial Photograph Collection. By using historical aerial photographs in a GIS, students were able to recreate large sections of these neighborhoods and compare change over time.

Historical GIS is a practice within the larger field of digital humanities (or as Ted Underwood recently described it using digits to understand the humanities). Richard White considered GIS a key part of the “spatial turn” in the humanities, and he argues that HGIS researchers often uncover more than they give themselves credit for. My students made innovative use of this new methodology to uncover the systemic racism of modern urban developments, from highways to university campuses. However, they emphasized the human stories behind the data. They recognized that a historical GIS is essentially a system for storing information and making maps, two skillsets that were pretty well codified in the early enlightenment. For all of its hype, HGIS is in many ways a computerized, map-enabled filing cabinet.

One of the central features of an historical GIS is to store and access large amounts of spatially explicit data. Like all historians, our filing cabinets collect a lot of information that will simply not appear in any way in a published project. The same is true for a GIS. Painstaking work on street-level, year-by-year data series can often result in a layer that is never published, or at least a layer whose historical attributes are not labeled or discussed. However, it is a tool that allows the historian to not only store the information but to process it and analyze it in completely unique ways. The new avenues for teaching environmental history and historical geography through digital history and projects like the CHGIS offer great promise for students of Canadian and other lost or changing landscapes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the students of HST 580: GIS for Historians for their excellent work on these communities. I would also like to acknowledge the help and advice offered by many colleagues and GIS professionals, including Nancy Dallett (ASU), Eric Feldman (Maricopa County), William Kyngesburye (KyngChaos), Tammy Parker (City of Phoenix), Matt Robinson (ASU), Jared Smith (Tempe History Museum), Patty Talahongva (Native American Connections), Mark Tebeau (ASU) Philip VanderMeer (ASU), Karina Wilhelm (ASU Map Library), Mary Whelan (ASU GIS Librarian).

[1] Scott W. Solliday, “the Journey to Rio Salado: Hispanic Migrations to Tempe, Arizona” (ASU MA Thesis, 1993), 123.