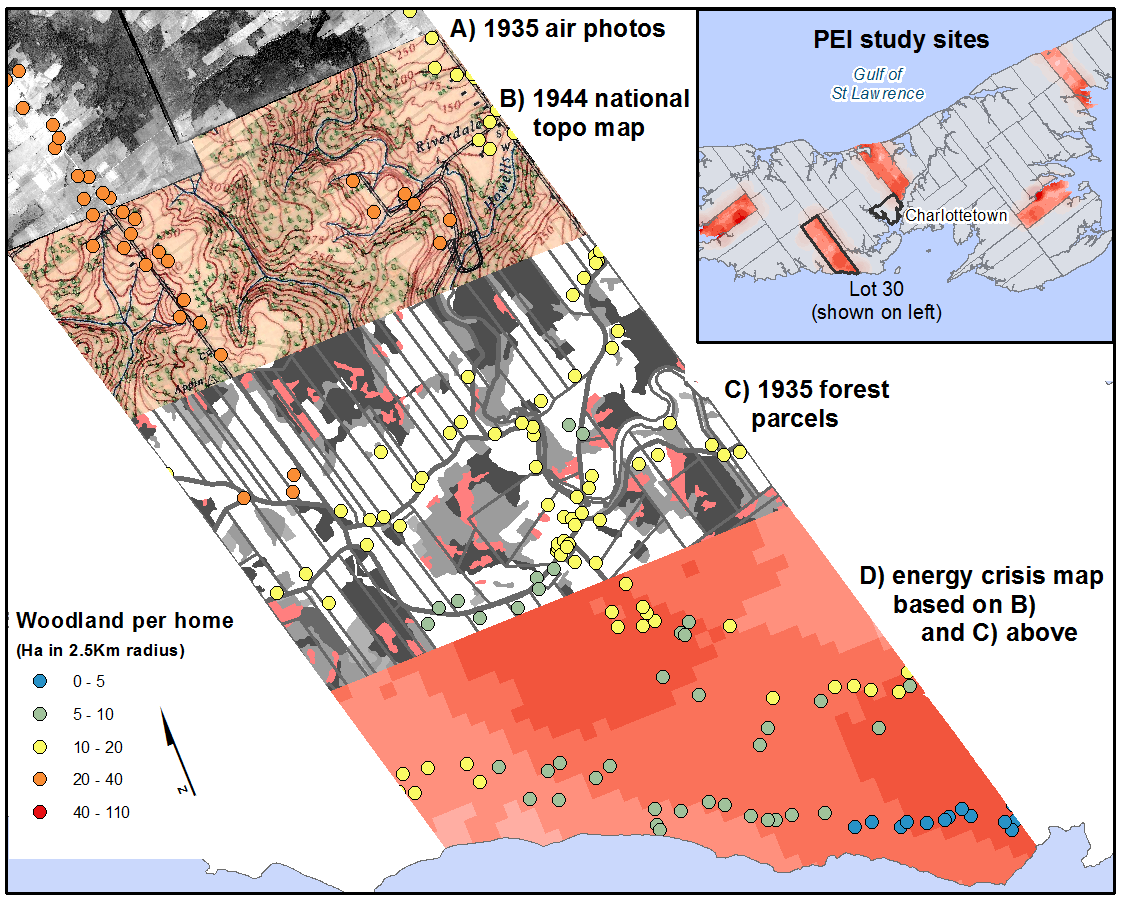

It is now common to read statementslike “Modern industrial agriculture is a disastrous failure, as it defies practically every natural law related to food cultivation, ecological and environmental protection and stewardship, and human nutrition.” But if this is true when did it begin, and why did new settlers decide to farm in this way? On this the last day of Spring, Real Time Farming looks back on the planting and other spring activities on nineteenth century farms like John MacEachern’s.

Photo: Josh MacFadyen

The earliest farmers in Atlantic Canada raised crops and livestock by maximizing the natural productivity of salt marshes. Wetland drainage was still a human disturbance, but at least it required limited deforestation. As population and farm settlement expanded the salt marshes represented only a fraction of the necessary caloric production, and farming became much more intrusive.

Since then, the farmer’s work has been to kill off, uproot, and fence out all of the biodiversity from an acre of land, and to plant and cultivate a single crop in its place. The old family farm might seem to us a distant sentinel of a lost way of life, but they were hardly timeless and uniform. Like all institutions that manufactured goods farms were dynamic systems and businesses, too. Decisions were based on complex variables such as climate, prices and markets, the availability of labour, community growth and decline, and changes in local diets and consumer demand. As petro-chemical fertilizers and pesticides became available they began to replace locally available soil treatments such as manure and mussel mud.

A progressively complex and experimental style of farming is visible in the diary of John MacEachern, who settled a farm in Rice Point in the mid 19th century. In the cold wet spring of 1866 MacEachern planted wheat, oats, clover, potatoes and a small amount of flax seed. Other work included building fences at home and markets in Charlottetown. The mare gave birth to a foal and the sheep were sheared for their wool.

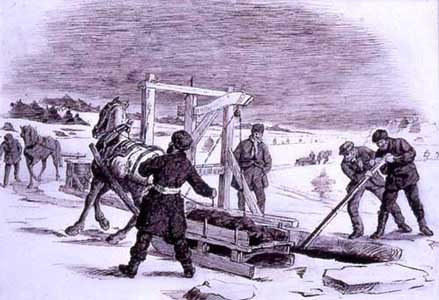

In 1879, the spring activities in Rice Point were much more diverse. The sheep produced another coat for the shearer in June, and John’s neighbours, Doug and Jane MacDonald, processed all or part of the wool. Pork was butchered for urban markets, fish were harvested from multiple locations, and MacEachern’s sons were busy with heavy work such as picking rock, hauling mussel mud and pulverising, planting, and rolling the new crops.

Photo: Josh MacFadyen

The crop selection was extremely diverse and reflected an ability to experiment with different plant varieties and methods of cultivation. Simple pulverising was replaced with “cross plowing,” harrowing, and pulverising crops before and after planting. Crop diversity increased, and even the grass seed used for hay included ТО lb each of Alsac, Dutch, and Red & White i.c., as well as “some Eng Red & White and ТН bushel Timothy.” Hay was a critically important crop for farms interested in increasing their ability to carry herds of cattle and sheep safely through the winter.

Other work in 1879 included fencing, cleaning seed, and cutting and burning “bushes” along the margins of the farm. These bushes were likely self-seeding conifers from the hedgerows and suckers growing on the stumps of cleared land.

A more interesting picture of the MacEachern’s farm landscape emerges in 1879, as John begins to think of his fields according to their locations and uses. The “bushes” and “new land” were located at the back of the lot and “outside of back fence,” and presumably the “new field” was either the same space or a field nearby. The “middle field” was on the water side of the house and had recently been lea, or pasture, and it was being pulverised and seeded to grass again in 1879.

Grass and oats fed the animals on this busy farm, and animals were essential for producing the potatoes, firewood, pork, and wool necessary to keep the MacEachern’s engaged in urban markets. Trips to “Town” were an important part of life in both the 1860s and 1870s, and the farmers made the journey both as producers and consumers. The city was the nexus for information and trade, and the most visible trend in the farm’s development was the increasing complexity of its market relationships. As MacEachern’s children came of age and became more available for farm labour, the extent of clearing, the complexity of cultivation, and the range of marketable products increased in turn.

Rice Point, PEI

May 1866

9, I went to Town for clover seed. Heavy rain.

14, I sowed wheat, five bushels

15 sowed 4 bushels of oats

16 sowed clover seed, 10 lb in 4 acres. Sowed 3.5 bushels oats on the upper turn hill and 2 lb red & white clover seed.

17. Rain showers and cold. This day 36 years ago we landed in Ch-Town the woods were green, no leaves yet. Dry now a week.

18 Sowing oats in lay land in swamp field at night mare foaled, 4 days less than a year.

19, Raining. Good fishing last week at Canoe Cove, slack at Nine Mile Creek.

24, Fine. Showry & finished sowing oats in swamp field, 15.5 bushels in 4.5 acres

25, Fine, Sheared the sheep & planted potatoes

26, Doug to mill with wheat

29 In the morning rain cleared up, I walked to ferry , to Town to Mr C W Rights

30, Overcast and raining, we planted potatoes

31 Fair, we planting potatoes, raw and cold this month.

June 1866

1, Fine, Doug and I to Town

3, Sab. Meeting in Canoe Cove

4, Sunny, the woods scarcely in leaf till this month

5, Rainy, we trucking poles to shore fence, sowed flax seed yesterday 1.5 pecks in the 1/8 of an acre

6, gloomy but mild, putting up shore fence

7, Telegraph dispatch from Canada on Sat eve last that Fenians from the Yankee’s side had encamped there…

Rice Point, PEI

May 1879

1 Thunder and a shower

2, Raw, I to Town by (Ftr, Ltr, Wr?) put note in bank, sent a letter to Cousin McFlet. & remins.

3, Warm, finished pulverising two ridges new land left in the fall

5 morning red, rain after breakfast boys went to haul mussel mud

6, foggy, Doug to Town R Ts, Potatoes 45 cents, I sifting wheat

7, misty, D & L hauling mud, Neil pulverising lea

8, I sowing wheat, 10.5 bushels below R.W.

9, Sowing Canadian clover, Alsac, Tim (Boston) on West side

10, I to Town for Eng. Clover & Alsac at Beer Brothers & Tim. & White to at Sellar’s. In the evening sowed Do in wheat, East side of field

13, I & Ln to Town, I across West River to J.W. Crosby’s

14, Hot, Neil finished planting Goodriches & Blue in lea land, middle field, below house, 4.5 acres.

15, Windy, Doug at field NW of house, oats 42 bu in 9.5-10 acres. Part pulverised before, and part after sowing.

16, I to Town paid Conr Bk by Cash from Cn day.

17, S. To W. Cloudy, N hauling potatoes & Lauchlin rolling oat field.

18, Sab. Minister Goodwill in C. C. Church.

19, Misty. 49 yeares today since we landed in Ch-Town out of the Brig “Corsair of Greenock,” passage about 45 days from port to port, the trees here were in full leaf, not so very early since.

20, Rained some last night. N.E. Misty, Neil plowing W Brookfield. E Side Doug sowed on Sat 13 Bushels. Evening, Minister in T. House, Text Galations 6: 7-10, an excellent sermon.

21 hauling stones off, near new land. Evening a heavy shower. Minister to Rocky Pt. Woods turning green now.

22 N. Cold. Sowed near back field, about 11 bushels. Evening cold and windy. Froze.

23 Ice on water at well. Doug & Christy to Town, took carcass of pork. I sowed near new field. Oats. Neil and Ln carting off stones. P. Aunt Julia came through woods.

24, NE. Blowy and cold, harrowing couch in lower W. Field for potatoes. Evening, Ln to Lobster Factory.

26, I sowing grass seeds in near Glenfield (Alsac ТО lb, Red & White i.c., Dutch ТО, some Eng red & White and ТН bushel Tim.). Rained PM fair, Neil at couch pulverizing, Doug harrowing grass seed.

27 AM W. Windy and cold and for some days past, very backward for vegetation, stormy for fishing, a thin skim of ice early

28 W. Windy, N&D finished cross plowing for potatoes, lower W field, dry. I burning trimmed bushes outside of back fence.

29 Hot & dry, PM rolling oats in new land & c.

30 AM calm, read Ezek Ch 16, Doug & Neil carting manure to lower W. Field, PM windy, much smoke from W. Dry.

31, W. Breezy & dry for some time, John McRae here helping to fill manure, day smoky & dry, hauled over 50 carts to K.

June 1879

1, Sab. Dry. Douglas the Bible C. Agent in Mg.

2, rained heavy before and after day break, much needed for crop & grass, cleared, D&N hauling M. Still from yard.

3, NE overcast, sent a letter to brother Neil in Buctouche h & one to Chas. Widow in Fredericton NB, we spreading manure for potatoes

4, AM some rain we began planting potatoes in lower W. Fields, some Pern on E. Then ten bushels Pr. Acre afterwards. Perusi & a drill or two Comptons, and a few Brooks, and some Scotch Victorias in two places, and 8 bushels rose potatoes.

5, at potatoes

6, at potatoes

7, a gale. We finished planting as above

8, Sab. A hail shower at day break, day cool

10, hot, Doug & Jane McDonald shearing our sheep, 36 sheep 14 lambs, 3 not altered.

11, J. McDonald washing wool

12, SE, Neil hauling poles across the brook for pasture. I levelling road, Doug at Donald’s at mud frolick

13, … heard that Lowther was writted for Oct. Court expences